© Mauro Baudino Collection - All rights reserved.

Studies

Handwriting study: learning to read Paul Mauser's scribbles

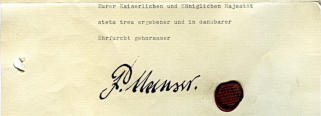

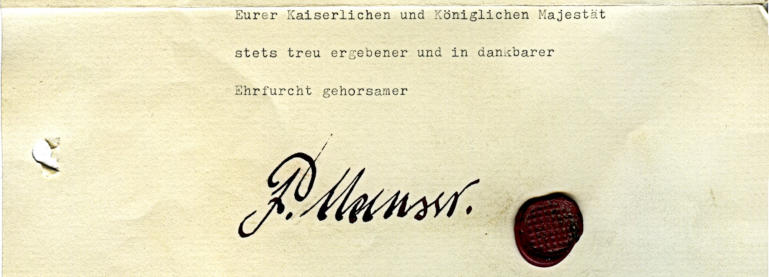

Studying old German handwriting is a bit of a challenge. Several styles existed of which the Sütterlin style is one of the worst to get to know. Paul Mauser was born and educated well before Sütterlin was introduced, which was a bit of an advantage. His handwriting is a variation of the Kurrent style, a handwriting style used for many centuries in Germany. The first samples of Paul Mauser's handwriting I worked with were found on the back of a letter from Georg Luger to Paul Mauser, dating from the early 1890s. Paul had scribbled his notes using a blunt blue pencil, which didn't improve things. The technique I employed was to work from a digital copy of the letter. This helped to preserve the original and it enabled me to zoom in and out, using a digital imaging program. This in turn helped to zero in on individual letters. Key to identifying letters is the isolation of commonly used (short) German words like 'die', 'das', 'und', etc.. Once the first words were identified, the characters were digitally copied to a chart and this way Paul Mauser's version of the alphabet was slowly completed. This chart with mappings of different characters in both upper- and lowercase variations was then used as a basis for further translation efforts. Interestingly, the writing style differed quite a bit when Paul switched from pencil to pen (ink) and back again. Also we see some changes in his style during several stages of his life. Paul had a serious eye- and hand injury in 1901 as the result of a testing accident with one of his repeating rifle prototypes. This accident (he lost one eye and damaged the other, as well as almost losing his index finger) had a lasting effect on the quality of his handwriting. A second chart with mappings of characters written with a pen was made as an aid for translating material written with pen and ink. The most challenging problem lies in the limitations of the reader (in this case myself), the reader has been taught his own writing style and he automatically 'translates' handwriting to the style embedded in his mind. We know what an 'a' looks like, and an 's', for example. Now, if we look at the Mauser files, we see that the 's' and the 'h' are written in a similar way, which resembles an 'f'. The 'e' is hardly recognizable as such, and the 'a' looks like something went horribly wrong with it. The 'o' exists in a very squashed form, resembling an undotted 'i' more than anything else. This means that you need to get accustomed to this shifting of familiar shapes and you constantly have to ban your knowledge of your own handwriting from your mind when trying to read parts. Like switching from one language to another, this takes a little time, but it gets easier with practice. Some examples: The shape of the letter 's' changes depending on the location of the letter in the word, and the sound it is meant to represent. When the words start becoming recognizable the next problem arrives: Interpretation and translation.Interpretation and translation

Paul Mauser ARCHIVE

© Mauro Baudino - All rights reserved.

Studies

Handwriting study: learning to read

Paul Mauser's scribbles

Studying old German handwriting is a bit of a challenge. Several styles existed of which the Sütterlin style is one of the worst to get to know. Paul Mauser was born and educated well before Sütterlin was introduced, which was a bit of an advantage. His handwriting is a variation of the Kurrent style, a handwriting style used for many centuries in Germany. The first samples of Paul Mauser's handwriting I worked with were found on the back of a letter from Georg Luger to Paul Mauser, dating from the early 1890s. Paul had scribbled his notes using a blunt blue pencil, which didn't improve things. The technique I employed was to work from a digital copy of the letter. This helped to preserve the original and it enabled me to zoom in and out, using a digital imaging program. This in turn helped to zero in on individual letters. Key to identifying letters is the isolation of commonly used (short) German words like 'die', 'das', 'und', etc.. Once the first words were identified, the characters were digitally copied to a chart and this way Paul Mauser's version of the alphabet was slowly completed. This chart with mappings of different characters in both upper- and lowercase variations was then used as a basis for further translation efforts. Interestingly, the writing style differed quite a bit when Paul switched from pencil to pen (ink) and back again. Also we see some changes in his style during several stages of his life. Paul had a serious eye- and hand injury in 1901 as the result of a testing accident with one of his repeating rifle prototypes. This accident (he lost one eye and damaged the other, as well as almost losing his index finger) had a lasting effect on the quality of his handwriting. A second chart with mappings of characters written with a pen was made as an aid for translating material written with pen and ink. The most challenging problem lies in the limitations of the reader (in this case myself), the reader has been taught his own writing style and he automatically 'translates' handwriting to the style embedded in his mind. We know what an 'a' looks like, and an 's', for example. Now, if we look at the Mauser files, we see that the 's' and the 'h' are written in a similar way, which resembles an 'f'. The 'e' is hardly recognizable as such, and the 'a' looks like something went horribly wrong with it. The 'o' exists in a very squashed form, resembling an undotted 'i' more than anything else. This means that you need to get accustomed to this shifting of familiar shapes and you constantly have to ban your knowledge of your own handwriting from your mind when trying to read parts. Like switching from one language to another, this takes a little time, but it gets easier with practice. Some examples: The shape of the letter 's' changes depending on the location of the letter in the word, and the sound it is meant to represent. When the words start becoming recognizable the next problem arrives: Interpretation and translation.Interpretation and translation

Archive Digitalization

The Archive digitalization is the first step for a serious analysis of the Paul Mauser documents. All the documents are sorted by year and then by type (diary, letters, notes, telegrams...). For each year a folder is defined. Inside it, several folders are associated for each type of document. Each folder contains the scan/picture of the document with the related translation. After this classification, the analysis and interpretation of the documents start. All the undated document are stored in the same folder. For some of them a tentative of dating could be done based on the content. If the content interpretation is accepted then the document is moved in the related year folder.

Paul Mauser ARCHIVE